Feeling stuck between “call a pro” and “I can probably fix this”? This guide walks you through five beginner‑friendly home repairs, step by step. Each one is designed for DIYers who want to build real skills, avoid repeat problems, and work safely with basic tools.

---

Before You Start: Safety, Tools, and When to Stop

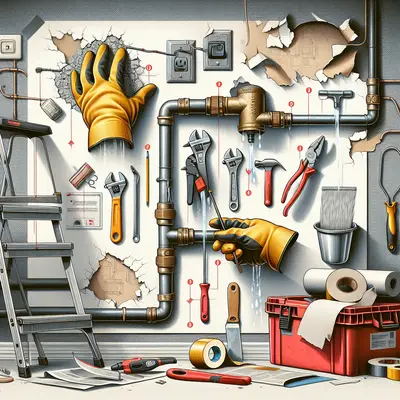

Before jumping into any repair, get clear on three things: safety, tools, and limits.

Turn off power at the breaker for anything electrical, and shut off water at the valve for anything plumbing‑related. Test that things are truly off: flip the light switch, run the faucet, or use a non‑contact voltage tester before touching wires. Wear safety glasses anytime you’re cutting, drilling, scraping, or working overhead, and use gloves when handling sharp edges or chemical products like caulk remover or paint stripper.

For most basic repairs, you’ll use a small core kit: Phillips and flathead screwdrivers, adjustable wrench, tape measure, utility knife, pliers, drill/driver with bits, stud finder, level, caulk gun, putty knife, and a basic hammer. Keep a small notebook or notes app list of materials (e.g., bulb type, filter size, screw length) so you buy the right replacements once and avoid repeat store runs.

Know your limits: if you see scorched electrical boxes, unknown wiring splices, structural cracks wider than a pencil, standing water where it shouldn’t be, or smell gas, stop and call a pro. A smart DIYer knows when the risk isn’t worth the savings.

---

Step 1: Fix a Wall Anchor That Ripped Out of Drywall

When a towel bar, curtain rod, or shelf pulls out of the wall, simply screwing it back in won’t hold. The surrounding drywall is usually damaged and weak. Repairing it the right way keeps the problem from returning and prevents bigger holes later.

Start by removing the loose fixture and any remaining screws or anchors. Use a utility knife to cut away torn paper and crumbling drywall around the hole until you reach solid material. You want a clean, firm edge, not fuzzy paper. Lightly scrape the surface with a putty knife to flatten raised areas.

If the hole is smaller than a quarter, fill it with patching compound or spackle, then let it dry and sand smooth. For larger holes, use a self‑adhesive patch or a “repair clip” kit as directed, then cover with joint compound in thin layers, letting each layer dry fully before sanding. The key is building up smooth, even layers rather than one thick, lumpy coat.

Once the wall is restored, skip the basic plastic expansion anchors that failed before. Instead, use heavier‑duty solutions: metal toggle bolts, self‑drilling anchors rated for the load, or ideally, screws into a stud. Use a stud finder to see if you can align at least one side of the fixture with solid framing. Finally, reinstall the towel bar or shelf, tightening screws firmly but not so hard that they crush the drywall or strip the anchors.

---

Step 2: Replace a Leaky Faucet Cartridge (Without Replumbing Everything)

A dripping faucet usually isn’t a failed “faucet”—it’s often a worn cartridge or washer inside. Replacing that internal part can stop the leak without touching any pipes or using a torch, making it a great DIY confidence builder.

First, locate the shut‑off valves under the sink and turn both hot and cold handles clockwise until snug. Open the faucet to relieve pressure and confirm the water is actually off. If there are no shut‑off valves, you’ll need to turn off the main water supply to the house, which is typically near where the main line enters the building or by the meter.

Plug the sink drain with a stopper or rag to keep small parts from disappearing. Carefully pry off any decorative caps on the faucet handle (usually marked hot/cold) with a small flathead screwdriver. Remove the screw underneath, then lift off the handle. If it’s stuck, gently wiggle and pull; avoid prying against the faucet body with force that could damage the finish.

Next, inspect the exposed assembly. Take clear, close‑up photos from multiple angles—these are your roadmap for reassembly and for matching parts at the store. You’ll typically see a retaining nut or clip holding the cartridge in place. Loosen the nut with an adjustable wrench or remove the clip with pliers, then pull the cartridge straight up. If it resists, a gentle twist can help break it free.

Bring the old cartridge, O‑rings, and any springs or washers to a plumbing supply store or big‑box home center to get the exact match; faucet parts are brand‑ and sometimes model‑specific. Reassemble in reverse order with the new parts, lightly lubricating O‑rings with plumber’s silicone grease if recommended. Turn the water back on slowly, check for leaks at every connection, and run the faucet through both hot and cold ranges to confirm the drip is gone.

---

Step 3: Silence a Noisy, Running Toilet

A constantly running toilet wastes a surprising amount of water and money. Most of the time, the fix is inside the tank and requires no special tools—just patience and careful adjustment.

Remove the tank lid and set it safely aside; it’s heavy and can crack if dropped. Inside, you’ll see the fill valve (usually on the left), the flapper at the bottom that opens to flush, and the overflow tube in the center. Flush once and watch what happens: where is the water escaping or misbehaving? Common issues are a worn flapper that doesn’t seal, a chain that’s too tight, or a fill level that’s set too high.

First, check the flapper. When the tank is full, gently press down on the flapper with a stick or handle. If the running sound stops, the flapper is likely leaking. Turn off the water at the shut‑off valve behind the toilet, drain the tank by flushing, then remove the old flapper by unhooking it from the posts. Bring it to the store to match the size and style (universal flappers work for many toilets, but not all).

If the water level rises above the overflow tube and then spills in, the fill valve needs adjustment. Many modern float mechanisms have a screw or a clip to raise or lower the water level. Aim for a water line about 1 inch below the top of the overflow tube. Adjust in small increments, turning water back on to test until the tank fills to the proper level without overflowing.

Finally, adjust the chain between the handle and flapper so there’s a little slack—enough for the flapper to sit fully down, but not so much that the handle travel is wasted. Turn the water back on, let the tank fill, and do multiple test flushes. Wait several minutes after each to ensure the running water sound is gone and the bowl water level is stable.

---

Step 4: Re‑Caulk a Moldy, Cracked Tub or Shower Joint

Old, stained, or cracked caulk around your tub or shower doesn’t just look bad—it can let water seep behind walls and under floors. Re‑caulking is a manageable DIY job, as long as you focus on preparation and drying time, not speed.

Start by choosing the right product: for tubs and showers, use a high‑quality, mold‑resistant bathroom caulk labeled for “kitchen & bath” or “tub & tile.” Silicone or siliconized acrylic both work; pure silicone is more durable and flexible, but harder to clean up. Avoid generic latex caulk meant for trim or drywall.

Use a utility knife or caulk removal tool to carefully cut and pull away the old caulk. Be patient—rushing this step leads to poor adhesion and new leaks later. Scrape off any remaining residue with a plastic scraper, taking care not to gouge the tub or tile. Clean the joint thoroughly with a bathroom cleaner or a mixture of vinegar and water, then wipe with rubbing alcohol to remove soap scum and oils. Let the surface dry completely.

Once dry, apply painter’s tape just above and below the joint to give yourself clean lines. Cut the caulk tube tip at a 45‑degree angle, starting with a small opening; you can always enlarge it if needed. Using steady pressure on the caulk gun, run a continuous bead along the joint, trying not to stop and start.

Immediately tool the bead by running a damp finger or a dedicated caulk tool along the joint in one smooth pass, pressing the caulk into the gap and scraping off excess. Remove the painter’s tape while the caulk is still wet so it doesn’t tear or pull cured caulk. Respect the manufacturer’s cure time—usually 24 hours or more—before showering or exposing the area to water, even if it feels dry to the touch sooner.

---

Step 5: Secure a Wobbly Interior Door That Won’t Latch Cleanly

A loose, sticking, or misaligned door is more than an annoyance; it can strain hinges, damage trim, and make your home feel poorly built. Many of these issues come down to loose screws, minor shifts in framing, or small alignment errors that you can correct with hand tools.

Begin by identifying the exact symptom: does the door rub at the top or side, fail to latch unless slammed, or spring open on its own? Close it slowly and watch the gap around the door. The gaps should be fairly even, with a slightly larger gap at the top hinge side to accommodate natural sag.

If the handle side rubs the frame at the top, the door is sagging on its hinges. Open the door and inspect the hinge screws on both the door and frame. Tighten all with a screwdriver—not a drill, which can strip soft screws. If any screws just spin without grabbing, replace them with longer ones (2.5–3 inches) that bite into the framing behind the jamb, especially in the top hinge. This often pulls a sagging door back into alignment.

For latch problems where the bolt doesn’t catch in the strike plate, do a visual test: close the door slowly and see where the latch meets the strike opening. You can mark the latch with a dry‑erase marker or painter’s tape, close the door, then see where it hits. If the misalignment is small, loosening the strike plate screws and slightly shifting the plate up, down, in, or out can be enough. Fill any exposed old screw holes with wood filler or toothpicks and wood glue before reclosing.

If the door still binds slightly along an edge after hinge and strike adjustments, you may need to remove a small amount of material. Mark the tight area with a pencil, then remove the door by tapping out the hinge pins. Use a sharp hand plane or sanding block to shave a little off the marked area, working evenly and checking often. Seal any freshly cut edges with paint or sealer to keep moisture from swelling the wood later.

---

Conclusion

You don’t have to overhaul an entire room to make your home feel solid and reliable. Fixing an anchor that ripped out of drywall, stopping a faucet drip, quieting a running toilet, renewing tub caulk, and straightening a stubborn door are all realistic wins for a careful DIYer with basic tools. Focus on preparation, safety, and doing each repair once the right way instead of fast.

As you build a track record of successful fixes, you’ll get better at spotting early warning signs and tackling problems before they become expensive. That’s the real value of home repair skills: not just saving money today, but keeping your space comfortable, functional, and ready for whatever you take on next.

---

Sources

- [U.S. Department of Energy – Energy Saver: Leaky Faucets and Plumbing](https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/fixing-leaks) - Explains how small leaks waste water and money, and why timely repairs matter

- [Family Handyman – How to Fix a Running Toilet](https://www.familyhandyman.com/project/how-to-fix-a-running-toilet/) - Step‑by‑step guidance and diagrams for diagnosing and repairing common toilet tank issues

- [This Old House – How to Recaulk a Bathtub](https://www.thisoldhouse.com/bathrooms/21015012/how-to-recaulk-a-bathtub) - Detailed walkthrough of removing old caulk and applying a long‑lasting new seal around tubs and showers

- [Lowe’s – How to Repair Drywall](https://www.lowes.com/n/how-to/repair-drywall) - Covers tools, materials, and techniques for patching various sizes of drywall damage

- [University of Missouri Extension – Home Maintenance and Repair](https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/gh3600) - General best practices for routine home care, safety, and when to hire a professional

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Home Repair.